ENTREVISTA || Eight decades after the defeat of Nazi Germany, and 75 years since the Schuman Plan was presented to make future war between France and Germany "not only unthinkable but materially impossible," the EU finds itself at a crossroads - what German historian Kiran Klaus Patel calls the "third refoundation" of Europe.

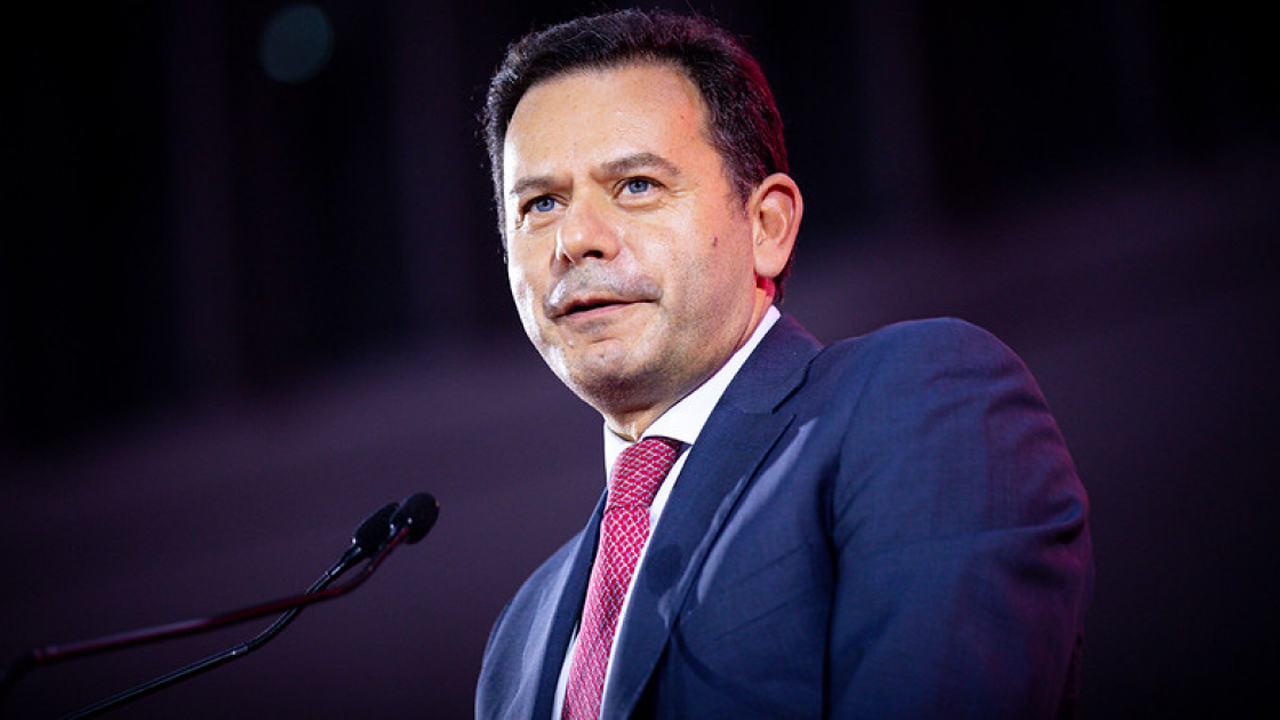

The interview was sparked by an opinion piece published by Kiran Klaus Patel, a professor at Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich and member of the Royal Historical Society, in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung about the 75th anniversary of Robert Schuman's famous speech, seen as the starting point for the EU as we know it.

To CNN, the historian speaks with some optimism about the future but calls for realism and more debates about the moment we are going through, and the tough decisions ahead. "I gave a lecture to 100 people and only one was aware of the White Paper with the Commission's radical plans for European defense."

Does the current situation in Europe and globally prove that history is cyclical? 75 years after the Schuman Declaration, are there more similarities or differences to be drawn between then and now?

The differences clearly prevail. Currently, relations between France and Germany are stable and, moreover, there is a long list of international organizations that have created close ties between European societies and others. In both cases, the situation was much more fragile in 1950. It is the broader framework and the potentialities that remind us of the past.

The world is in turmoil and the structures we currently have - and which were created at the time - are being challenged. New security threats have emerged. Karl Marx once said: History always repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce. At the time, great political efforts helped to avoid tragedy. This time, the situation is much worse than a farce, and we have to work hard to ensure that tragedy is avoided again.

You speak of the "visionary nature" of the Schuman Plan and say that "the fact that the unification process was not driven solely by idealism and visions has often been ignored, especially in Germany." What do you mean?

When talking about Europe, the Schuman Plan is usually associated with peace and reconciliation. And it was clearly motivated by those visionary and noble intentions. But there was also something else. When the French Foreign Minister presented his proposal in the spring of 1950, all previous French plans for Germany had failed - plans that had less to do with reconciliation and acceptance, at least on its western side and of an equal partner.

Moreover, the plan was intended to prevent a situation where the more competitive German coal and steel industries overtook the French ones. By placing the two sectors on the same level, integration thus represented French economic interests. Finally, integration à la française was intended to secure France's European and world role. Beyond ideals, it was (geo)political and economic interests that motivated the plan. We have to consider these two dimensions.

The dissolution of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 2002 marked another important moment in terms of the roots and evolution of the European Union. You say that this dissolution took place "at the height of neoliberal thinking," when the idea of this community seemed "a relic of times past," but today it seems to be considered visionary again. To what extent was it a mistake to dissolve the ECSC?

The ECSC represented more intervention and distribution than the European Economic Community (EEC), which became the most important dimension of the entire European project from the 1960s onwards. In the 1990s, when the decision was made to discontinue the ECSC, its approach had gone out of fashion. Coal and steel had lost their importance and some of its elements were absorbed by the EU. In contrast to the 90s and 2000s, we now see more calls for solidarity and for shared and strongly integrated projects in the EU. Through the back door, some of the lessons of the ECSC are becoming relevant again.

The economy has been the gravitational center of European integration - but now, more than ever, Europe seems to be transforming towards some kind of Defense union. A first attempt to create a European Defense Community (EDC) failed decades ago, notably when it was rejected by the French National Assembly, seen as a large-scale transfer of sovereignty in an area too important, thus politically unviable. To what extent is it politically viable now, considering that we can no longer count on US support as before and given the growing threats we face?

It will continue to be difficult and I do not think we will have an EU army in the foreseeable future. The decision-making mechanisms among Member States are very different when it comes to issues of war and peace. Moving to some kind of defense union would be a real qualitative leap. But let's not forget: many Member States are reluctant to cede so much sovereignty to Brussels. Another more realistic thing is enhanced cooperation in armament projects and in the creation of industries necessary for defense.

To what extent has the spirit of the EU changed since the Schuman Plan? You cite Luuk van Middelaar, when he says that, "since the Schuman Plan, the goal was to depoliticize politics" in the EU, for example, focusing on "carefully reached compromises" rather than on a "politics of the absolute." However, in some important areas, the EU still relies heavily on "absolute" support, i.e., consensus and not majorities. Many experts have argued that, in the face of the behavior of some Member States, the EU treaties should be amended to allow majorities instead of consensus. What is your opinion on this matter?

The EU continues to be based on a culture of compromises and on the depoliticization of politics. It often seems very slow and bureaucratic. That said, it is these qualities that make it so reliable. Trump's enigmatic policies recently reminded us of the alternative - and the high economic, social, political, and emotional costs of such an option. This is the broader framework.

Regarding specific powers: yes, there are some areas where "absolute" support is a prerequisite for EU action, as you well said. In recent decades, the number and scope of these policy areas have decreased. However, some of them are vital, such as Defense. Honestly, I do not think most governments are willing to give up their powers on such vital issues. In this area, realism is needed. NATO is not dead and meaningful Defense in Europe is only possible if it includes the UK. On Defense, I therefore think we need more creative formats than those currently in place in the EU.

Taking up a question you raise in your article: has the model outlined by Schuman finally entered into crisis?

It is in crisis, but it is certainly not dead. It can still be a successful formula if Europeans can see its value - and consider the alternatives.

We are faced with some visible changes in European thinking, such as the fact that Nordic countries seem more willing than ever to support and contribute to common funds or the fact that we now have the highest number of positive opinions on EU membership since 1983. Will these be good indicators that the EU will emerge stronger from this crisis? What does History show us in this regard?

This is an important change. Until now, common funds - especially common debt - have been an anathema to most of these governments. But, again, I also see a lot of path dependence: they are not asking for an EU army, but shared armament projects. This is in line with the EU's economic DNA and could lead to a revival of the Schuman method.

The problem with this "third refoundation of the EU," in your opinion, is that no one is having the debates that are really necessary. What debates are these?

The changes the EU is currently undergoing go very far and some of the plans proposed are truly breathtaking. But where is the debate about this? In the European Parliament? In all Member States? I recently gave a lecture to an audience of 100 people and only one person in the room was aware of the Commission's White Paper with its radical plans for European defense…

You mentioned earlier the need to include the UK in the EU's current defense efforts. In just over a week, we will have the London Summit and everything indicates that the post-Brexit defense and security pact to be negotiated between the two parties could collapse if the British government does not make concessions on issues considered "sensitive" by several Member States, notably regarding fishing rights. Are you optimistic about an agreement? How absolute is this need to have a security partnership with the UK?

Starmer and his Government want to establish new ties with the EU, especially on Defense. But their situation is very difficult domestically. Nigel Farage's Reform UK [populist and Eurosceptic party] is putting them under great pressure, especially on issues like fishing rights, i.e., issues of minor economic importance to the British economy, but very important to national identity. The best we can hope for are face-saving compromises, which move things forward without being too bold. It's not exactly what we need. But it's something typically European.

After weeks waiting for Friedrich Merz's official inauguration as German Chancellor, after the CDU concluded a governance agreement with the SPD, the conservative was only elected on the second ballot in the Bundestag. Does this weaken him as leader of the EU's largest power? What can we expect from Berlin in terms of European integration and the challenges the bloc faces with Merz at the helm?

Merz's path to the chancellery was bumpy. He is more committed to European integration and wants to make international affairs one of his main areas of action. That's good. But his political base in the country is fragile. His Government had a weak start - I would say things can only get better.

Comments

Join Our Community

Sign up to share your thoughts, engage with others, and become part of our growing community.

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts and start the conversation!